RESEARCH BOOK

The Difficult Heritage Of A Broken Past

YEAR

2019

The Difficult Heritage Of A Broken Past: Yugoslavian Post War Monuments is a research book following the monuments from their birth to their ideological death. It is a brief introduction into the turbulent history of the Balkan region, talked about through the monuments’ shifting narrative in relation to the changing power structures.

Viewing them as political propaganda, the book supports this claim by a conducted research, analyzing the benefactors and funding for individual monuments. The analysis was conducted on 42 randomly chosen monuments.

The book lays a theoretical foundation for ‘A Memorial To The Monuments’, a 9 screen video installation reconstructing their historical narratives through archival footage.

For more on the project click here

Introduction

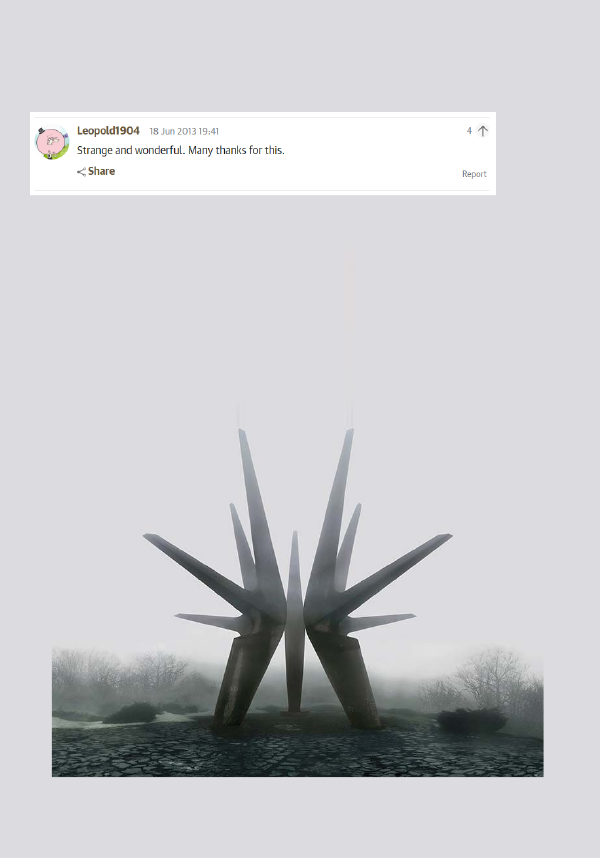

Kempenaers, Jan. “Spomenik #8 (Ilirska Bistrica).” Jan Kempenars, 2007, www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/6/

Yugoslavian post

war memorials are a series of monument structures, built between the 1950s and

1980s. They are a legacy of a bygone era, the embodied ethos of a generation,

objects of anger, and witnesses to suffering. They are triumphant and most of

all, they are misunderstood.

Following the

dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1992, many of these structures have been destroyed.

During the Balkan Wars between 1991 and 2001 they became symbolic targets for

anti-Yugoslav sentiment. Those that survived were in many cases neglected and

vandalized.

After decades of

damage and decay, something strange happened. In recent years they have gained

a lot of online attention, they became viral clickbait. They are often referred

to as being abandoned and forgotten or lumped together under the catch-all

title of “communist monuments”. The Western media dubbed them “spomeniks”, a bastardization

of a Serbo-Croatian word “spomenik” meaning monument. The term was first used

by Jan Kempenaers in 2006 as the title of his photobook documenting these

monuments. By completely decontextualizing and stripping them of all necessary

tools for understanding them, Kempenaers focused on the obvious – their awe.

_

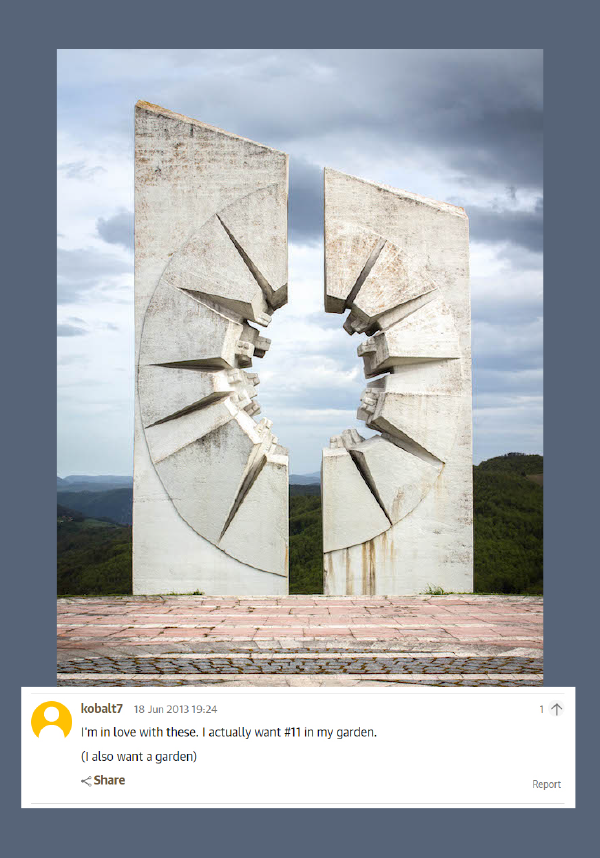

The book was the

start of their exoticization and the treatment of them as mute, incomprehensible

objects of a

foreign past (calvertjurnal.com). The pictures of the monuments spread

like wildfire on the internet, often presented as alien like futuristic

structures, with the term “spomeniks” commonly used. Because these monuments are inherently

political, the foreign given name can be seen as problematic, as it helps to

otherize them. It also highlights a Western perception of the Balkans as only

peripherally associated with the project of Enlightenment in the Western world.

As historian Maria Todorova states in her study ‘Imagining the Balkans’, the narrative of the Balkans as Europe’s internal “other” dominates the history of the region’s representation in Western art, literature and culture (3-12). It presents a mystified story, a spectacle of timeless and incomprehensible cycle of passion. “The old binary model of centre and periphery of cultural production has produced a skewed and deeply problematic outlook onto history” (Stireli and Kulič, 7). Any serious evaluation of cultural production in the region has been further hindered by a sense of Orientalism to “Spomeniks” and works like them, when talked about solely from an outsider’s perspective. This notion of the Balkans as Europe’s “orient”, an exotic “other” territory between East and West, needs to be challenged. It often leads to misrepresentation of the region’s culture, one that evokes a sense of cultural imperialism.

Kempenaers, Jan. “Spomenik #3 (Kosmaj).” Jan Kempenars, 2006, www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/25/

Under postmodern

political conditions, a neoliberal notion of plurality of cultures, or

multiculturalism, has come to light. It is through these cultures an individual

becomes, according to Laclau and Mouffe, an ensemble of “subject positions”

rather than one moment or instance of a larger collective identity (11-15). As

no culture relations can ever be truly neutral, multiculturalism involves a

Eurocentric distance and/or respect for local cultures not rooted in one’s own

culture. This “respectful” distance from which one is able to appreciate other

particular cultures involves a patronising gaze, one that requires a “neutral”

approach to that which you want to document or protect (Tomney, 2). Doing so

involves asserting one’s own superiority, revealing multiculturalism as a

version of cultural imperialism of the multinational capitalist model.

This view is

especially evident in the case of the memorial monuments. In order to avoid asserting blatant sentiments

of cultural superiority, the Western media confronts them with a sense of

“neutrality”. As a result they are often completely de-contextualized, stripped

of any political and cultural connotations, and left without any indication of

what they commemorate. Confronting them on a surface level leads to articles

such as “Spomeniks: the Second World War monuments that look like alien art.

The author, Joshua Surtees, states: “… the British equivalent would be Harold

Wilson

_

commissioning Henry Moore to create war memorials and dotting them all

over Britain in the least visited places” (theguardian.com). This amusingly

misguided observation, points towards a complete lack of understanding.

As a result these

places of remembrance became concrete clickbait. A shared Yugoslav experience

of a revolution became only a cultural artefact used to boost online traffic. A

better way to engage with these monuments would be to use them as a tool to

re-connect to the near past, reviving whatever can be found of politics and

aesthetics of a particular era. To do so, we need to go past the nostalgia and

past their sheer fascination. We need to face them as mediating factors between

the constructions of past narratives, collective imagination and political

activities of the present moment.

Political context

Kempenaers, Jan. “Spomenik #16 (Tjentište).” Jan Kempenars, 2007, www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/14/

Immediately

following WWII the newly formed Yugoslavia politically aligned itself with the

Soviet Union, although the alignment didn’t last long. In the late 1940s, the

relationship between Yugoslavia and the USSR became strained as Tito refused to

make Yugoslavia a Soviet satellite state within the Eastern Bloc.

At the outset of

Tito’s new Republic ambitious plans were laid to create a classless country

ruled by principles of socialism, a population free of ethnic tension all bound

together by feelings of “brotherhood and unity”. It was a paradigm of a utopian

project, one geared to the creation of a pluralistic, secular and idealistic

society (Stireli and Kulič, 8). The Federal and multi-ethnic state provided a

structure of cultivating internal multiculturalism, a distinct feature of the

post-war Yugoslav project. Comprising of numerous ethnicities, some of which

have been engaged in bitter conflict during the war, Yugoslavians would be

unified around a sense of progressive optimism held together by a collective

righteousness in their victory against fascist aggression.

_

Distancing itself from the USSR, post-war Yugoslavia searched to legitimize itself by claiming to pursue emancipation: internally, from class divide and ethnic conflict, and externally, by supporting anticolonialism. Pursuing friendly relations, cultural connections and economic exchange with both rival blocs, it became a country which offered a “third way”, an alternative to the capitalist West and communist East. By deliberately defying the geopolitics of the East-West divide and its unique presence at the intersection between the two it enjoyed an outsider’s international presence. This created a stage on which to exchange architectural knowledge and ideas, across political borders and cultural divisions (Stireli and Kulič, 7).

Intentions

Kempenaers, Jan. “Spomenik #18 (Kadinjača).” Jan Kempenars, 2009, www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/16/

During the initial

decade after the war, some monuments were commissioned across Yugoslavia,

crafted in the traditional “socialist –realism” style. The key aspect of the

style was the notion of “typical”: a typical protagonist in a typical situation.

Not in the sense of presenting reality but as elements of fantasy, “typical” was

an intangible support to the ideology of communism. (Žižek, “Multiculturalism, Or, the Cultural Logic of

Multinational Capitalism” 28) It often depicted

intense and graphic imagery focused on evoking feelings of the past horrors,

old suffering and forgotten crimes. Trying to suppress ethnic nationalism for

the sake of national unity and cultural cooperation, it was feared that such

monuments might evoke unwanted tensions.

After the

countries split from the USSR the government wanted to emphasize the departure

by finding its own visual language, looking for inspirations in the artistic

movements of Western Europe and America. As architects were freed from

historical mandate of social realism, the singular architectural style of a socialist

society until that point, anti-fascist WWII sculptural memorials began to

spring up across Yugoslavia in the styles of abstract expressionism, geometric

abstraction and minimalism.

_

The structures did

not only represent a departure away from Soviet thinking, but were also

designed to celebrate universal ideals, such as “brotherhood and unity”.

Yugoslavia created a series of distinctly “Yugoslavian” monuments used as a

tool to blaze a unique identity for the nation.

Between the 1960s

– 1980s hundreds of these monuments were built across all six republics of

Yugoslavia; Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Socialist Republic of

Croatia, Socialist Republic of Macedonia, Socialist Republic of Montenegro,

Socialist Republic of Serbia and Socialist Republic of Slovenia. Their primary

intent was to honour the regions struggle during the National Liberation War (WWII).

Many felt that commemorating this through decontextualized abstraction might

aid the country in ethnic and religious reconciliation, by creating spaces for

solace, reflection and forgiveness for all.

The resulting body of

work can broadly be identified as modernist for its social and aesthetic

aspirations, but at the same time it adds a different dimension to that general

category. They do not operate only as surreal and abstract structures

memorializing a horrific past, but additionally they function as political

tools meant to articulate the countries vision of a new tomorrow.

Question of propaganda

Question of propaganda

Whether these monuments

were political propaganda or not has been a subject of debate within the region’s

academic community for years, enticed by the growing interest in human

collective and cultural history of the region. Some scholars argue that the

style of the monuments was just a natural response to the countries departure

from the USSR and embracing cultural exchange with the West. Through the 1920s

and 1930s, many Yugoslav architects would study or work in offices abroad, a

tradition that was revived in the 1950s and 1960s. This time this was enabled

through aid and grant programs funded by Western nations to carry political

influence and strategic partnership with a country without any clear political

affiliations.

This narrative can

be further supported by quickly glancing at where the funding for individual

monuments came from. While some projects were approved for funding by the

federal government, and some even visited by president Tito on their official

public unveiling, some were raised using voluntary donations only. To

illustrate this point the case of Bosnia’s Mount Kozara is often used. Although

it is true that the monument was founded entirely by public donations, it is

important to note that the site was officially recognized for its historical

significance by the SR of Bosnia in 1957 with plans for a massive memorial

complex already starting to take shape. Five years later a 38 member selection

committee was formed to initiate the open call, which included several

government officials.

_

On the other hand,

many scholars claim that they were created as political propaganda. This

argument finds its basis in the sheer amount of monuments being built in a

similar style in a relative small amount of time. Experts claim that this kind

of cohesion is highly improbable not to be planed, especially in the historic

and political context of the time. Moreover, the project of Yugoslavia was one

of trying to unify different ethnic groups that have during WWII experienced

deadly conflicts. It tried to bring together the recently defeated Yugoslav

Axis collaborators and Partisans. This would only be possible through processes

of exclusion, exclusion of violence and memories too painful to commemorate. It

is in that sense, that these memorials can be regarded as political, as they

are the expression of a particular structure of power relations.

Finding an

objective and conclusive answer for this question is next to impossible. The

biggest problem being that the resulting successor states have spent the past

20 years rewriting history, including art history, to fit their individual

national narratives. As a result, many or all sources may be untrustworthy as

they paint a subjective picture of the past.

Although there are

archives of these monuments, most of them focus on their historic aspect,

location and the year they were built. Their corpus has never been observed as

a whole, and even more importantly, it has never been observed from a certain

historic distance.

The following research takes forty-two randomly selected

monuments from different sources, and instead of focusing on their history,

looks at who commissioned them and who paid for them. As some of the monuments

took up to 10 years to build, the research also looks at when their plans were

approved, instead of when they were finished and revealed to the public. By

cross-examining where the money came from, the conducted research hopes to

provide an insight in this highly debated topic.

The researched

monuments are here presented over the next twenty-three pages chronologically.

Focussing on three decades – the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Each decade is

internally organized in three categories: early, mid and late. A colour code

has been created for an easier overview. Consisting of eight categories, each

of them represents a source of commission and/or founding: Tito, federal

government, regional government, local government, local communist parties,

veteran groups, voluntary public donations, privately donated funds. The

colours represent the level of the country’s involvement for each of the

monuments and are visualised as their background.

Due to the lack of

transparency surrounding many of the monuments, there is no known data on who

commissioned or funded a couple of them. These are represented in the research

without a background but kept to provide a full picture.

_

When viewed together, the collected

data reveals an interesting pattern. Although projects funded by the federal

government weren’t limited to any specific decade, there is a clear difference

in funding between the years directly following Yugoslavia’s departure from the

USSR and later decades.

It becomes clear that the initial

wave of monuments built through the 1950s was solely overseen by the federal

government. That trend was somewhat carried through the early 1960s, when the

projects seemed to be taken over by the regional and local governments.

Although these governments were autonomous to some extent, they still received

monetary support from the federal government and had to work within certain

guidelines.

An interesting quote comes from a

2008 interview with Bogdan Bogdanović, a prominent Yugoslav architect and

author of many of these monuments. Talking about the very long process of

finding a suitable design for the Jesenovac monument in Croatia, he states:

“Tito, in all truth, did not have much artistic discernment. But he understood

that my monuments were not Russian monuments (at that time, unfortunately, all

the best sculptors have adopted the Russian formula: headless bodies, wounded

figures, stretchers). When he saw me, a bizarre man with a surrealist

biography, ready to build him constructions which weren’t Russian, he said,

“Let him”.” This signifies Tito’s understanding of ideological and political

significance of maintaining appearances and their profound effect on the

socio-symbolic position of those concerned.

_

It is also important to note that

in their heyday, the Yugoslav memorial sites formed a physical network of

education and memorialization centres, spread out across the six republics.

Often the memorial complexes were fitted with museums and a central feature of

many were amphitheatres. Busloads of school children would visit as part of

their history curriculum or via Tito’s “Young Pioneers” political youth

initiative.

The monuments acted as outdoor classrooms, used as a tool to communicate the

history, mythology and ideology of the country. They were a national network of

grand teaching tools for relating to the population the ethos, history and

narrative of Tito’s Yugoslavia.

Cross-examining the gathered data,

a possible interpretation starts to emerge. Right after Yugoslavia’s split from

the USSR, the first wave of monuments was completely government funded. This

suggests that they were inherently propaganda. From their drastically different

style to their sheer size, they were a clear statement about the countries

shifting alliances, a not so subtle nod to the West. Even though not all

monuments were government projects in the following decades, the initial wave

had such a strong impact that it firmly cemented a new visual language.

Political propaganda became a nationwide trend, creating a new socialist style.

When viewed as a single unit, they tell a story of external political

propaganda, and stand as a testament to cultural planning and one nation’s

intent to communicate a shared ideology.

Cultural genocide

Kempenaers, Jan. “Spomenik #15 (Makljen).” Jan Kempenars, 2007, www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/3/

Since the

dissolution of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, many of these monuments have fallen

into disrepair. The relative political stability of post-war Europe was

achieved through a generalized forgetting of wartime crimes. This proved to be

too difficult of a task for the people of Yugoslavia. From 1991 to 2001, the

Balkan region was overtook by ethnic conflict and re-emergence of politics of

pure particularism, one that manifested itself in the form of extreme

nationalism.

The change of the

ideological paradigm caused the necessity of creation of new memory politics

and rewriting of recent history, a method that is widely referred to as

historical revisionism. This involved processes that can be read as iconoclasm,

the erasure of monuments of the fallen regime (Horvatičić, 00:05:29-00:05:40). The

resulting nationalist movements saw the monuments as unwelcome symbols of a

unified Yugoslavia, resulting in them being destroyed, abandoned and neglected.

They were discredited as “communist”,

instantly erasing their history of commemorating the victims of fascism and the

antifascist struggle of World War II.

It has been

reported that by the turn of the millennium, more than 3000 memorial grounds

have been vandalized or destroyed across the Balkan region.

_

These acts of violence were largely carried out during night time, out of sight of the

general public. While most of these instances weren’t reported on, those that

were, are now considered to be cover up stories. Following the destruction of

one of the abstract monuments in Slavonia, a local newspaper reported that the

concrete memorial complex was destroyed by strong winds (Šuljič, “Minirani

partizani” 68).

Moreover, the

successor states stripped the monuments of their status as cultural monuments,

a status they were given in Yugoslavia. This meant they no longer were protected

by the state and became no one’s property. They

were rendered out of mind. Those that still remain tell a hunting and

passionate story about violence, history and future unrealized. They stand

silently as a ruined web of unseen cultural markers.

There is no doubt

that the monuments have had a very tumultuous life. From being adorn and

celebrated for decades, to their demise in the 90s, and recently being

rediscovered as cultural commodity. This sort of shift in narrative is very

unusual, especially in historic monuments commemorating war struggles. How did

these monuments that were meant to heal a region and help overcome ethnic

rivalries through benevolent forms, become artefacts of contention?

Walker, Alan “a still from music video Darkseid” Youtube, 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=M-P4QBt-FWw

Following the terrors experienced during WWI and WWII, a major part of the 20th century mind-set and social investment was in the protection of memory, with WWII memorials being the most obvious case. Almost all Western war memorials of the period tend to shy away from depicting aggression, not showing the war as it actually was. One could argue, that since the Yugoslavian post war monuments do not only follow the aesthetic but also sociohistorical tendencies of the modernist monument, they should be considered as part of a larger corpus of Western memorial production.

So why have they

experienced such a drastically different fate then the likes of the Memorial to the Fallen Jews of Europe in

Berlin, or the Aschrott Fountain in Kassel? Perhaps the answer lies in the

historic and political context in which they were erected. As previously

established, they weren’t only spaces of solace and recollection, they also

acted as political tools, a role more closely related to monuments of

totalitarian regimes. And how better to celebrate the fall of totalitarian

regimes than by celebrating the fall of their monuments.

It is important to

note that there is a clear difference in the role the Yugoslavian monuments had

as political tools, then that of the Soviet monuments. The Soviet monuments

acted as internal propaganda, enforcing the Communist Party’s ideology of a

heroic proletariat and glorifying the Party’s leaders. In contrast, Yugoslavian

monuments were an act of external propaganda, emphasizing the countries

departure from the Eastern Bloc.

_

As such, they didn’t operate with the motifs

of idolization, but focused solely on the memorialization of the victims of WWII.

Therefore they shouldn’t have experienced aggression after the fall of

Yugoslavia.

Perhaps the reason

for their fate is the benevolence itself. Since there was concern that more

direct and aggressive forms might evoke feelings of suppressed horrors and

forgotten suffering, which would lead to ethnic tensions, the government

decided to adopt a less representative, more abstract style. When looking at

them through a historic prism, it seems that leaving out the aspect of violence

rendered them, while still important and impressive, empty vessels.ć

As the years after

the war passed and the memories became less painful and less clear, the

monuments took on a new role. Because of the lack of a strong visual

implication of what they were supposed to commemorate, people could project

their own sentiments onto them. In the nation’s eyes, they became the

embodiment of the Yugoslav ethos and its symbols. This notion was carried

through into the 90s, when they became targets of nationalist aggression and

faced neglect and destruction.

Even now,

rediscovered by the internet, this lack of clear communication, has left them

somewhat unreadable and vulnerable to commodification. They became silent

backdrops for magazine photoshoots and music videos, exploiting them for their

impressive visuals. Their online status as cultural icons becomes apparent when

searching the #spomenik on Instagram, with more than 16.000 results. Most

interestingly, a large portion of the posts using the hashtag isn’t about the

monuments at all. This implies that the monuments became an online brand, one

that is reduced only to boosting online traffic.

Perhaps this fate

could have been avoided with a clearer narrative. By not shying away from the

violence and pain, they would present a less ambiguous sentiment, standing firm

in what they are and not what people perceive them to be. Perhaps if they

embraced the violence, they would have survived.

Bibliography

Blau, Christine. “Haunting Relics of a Country That No Longer Exists”. National Geographic, 28 Aug. 2017, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/destinations/europe/former-yugoslavia-monuments/. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

“Brutalist

Socialist-era Yugoslavian Monuments – the Spomenik”. Yomadic, 20 Jun. 2016, https://yomadic.com/yugoslavian-monuments-map. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

Čakarić, Nina.

“Koga sploh (še) zanimajo jugoslovanski spomeniki revolucije?”. Delo, 1 Nov. 2016, https://www.delo.si/novice/slovenija/koga-sploh-se-zanimajo-jugoslovanski-spomeniki-revolucije.html. Accessed 29 Jan, 2019

Forty, Adrian. “The Art of Forgetting”. AA Lecture Series, 15 Oct 1998, Lecture Hall, London. Lecture

Hatherley, Owen.

“Concrete Clickbait: Next Time You Share a Spomenik Photo, Think About What it

Means”. The Calvert Journal, 29 Nov.

2016, https://calvertjournal.com/articles/show/7269/spomenik-yugoslav-monument-owen-hatherley. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

Horvat, Marijan. “Rehabilitacija Ustaštva”. Mladina, 29 Apr. 2016, pp. 44-48

Horvatinčić, Sanja. “Genealogy of Form: Typology of the Monuments to

People’s Liberation Struggle, Revolution and the Labour Movement in Croatioa”. Art for Collective Use: Monument,

Performance, Ritual, Body, 10 Nov 2015, Faculty of Arts, University of

Ljubljana. Lecture

House, Arthur.

“State of the Art: Rethinking Yugoslavia, the Dictatorship That Embraced

Conceptualism”. The Calvert Journal,

29 Jan. 2016, https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/5354/yugoslavia-art-nottingham-contemporary-monuments-should-not-be-trusted-lina. Accessed 9 Jan, 2019

“Brutalist Socialist-era Yugoslavian Monuments – the Spomenik”. Yomadic, 20 Jun. 2016, https://yomadic.com/yugoslavian-monuments-map. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

Čakarić, Nina. “Koga sploh (še) zanimajo jugoslovanski spomeniki revolucije?”. Delo, 1 Nov. 2016, https://www.delo.si/novice/slovenija/koga-sploh-se-zanimajo-jugoslovanski-spomeniki-revolucije.html. Accessed 29 Jan, 2019

Forty, Adrian. “The Art of Forgetting”. AA Lecture Series, 15 Oct 1998, Lecture Hall, London. Lecture

Hatherley, Owen. “Concrete Clickbait: Next Time You Share a Spomenik Photo, Think About What it Means”. The Calvert Journal, 29 Nov. 2016, https://calvertjournal.com/articles/show/7269/spomenik-yugoslav-monument-owen-hatherley. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

Horvat, Marijan. “Rehabilitacija Ustaštva”. Mladina, 29 Apr. 2016, pp. 44-48

Horvatinčić, Sanja. “Genealogy of Form: Typology of the Monuments to People’s Liberation Struggle, Revolution and the Labour Movement in Croatioa”. Art for Collective Use: Monument, Performance, Ritual, Body, 10 Nov 2015, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana. Lecture

Laclau, Ernest and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. London:

Verso, 1985

Niebyl, Donald. Spomenik Database, 2015, https://www.spomenikdatabase.org.

Accessed 5 Jan, 2019

Niebyl, Donald. Spomenik Database, 2015, https://www.spomenikdatabase.org. Accessed 5 Jan, 2019

Richer, Darmon. “The Misunderstood History of the Balkans’ Surreal War

Memorials”. Atlas Obscura, 6 Nov.

2017, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/spomenik-memorials-yugoslavia-balkans. Accessed 9 Jan, 2019

Stierli, Martino and Vladimir Kulić. Toward

a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948-1980. The Museum of

Modern Art New York, 2018

Surtees, Joshua. “Spomeniks: The Second World War Memorials That Look

Like Alien Art”. The Guardian, 18

Jun. 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/photography-blog/2013/jun/18/spomeniks-war-monuments-former-yugoslavia-photography. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

Šuljić, Tomica. “Minirani Partizani”. Mladina, 21 Apr. 2005, pp. 66-70

Šuljić, Tomica. “Spoštuj vse mrtve”. Mladina,

6 May. 2005, pp. 17-19

Tormey, Simon. “Do we Need “Identity Politics?” Postmarxism and the

Critique of “Pure Particularism””. Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions workshop on ‘Identity Politics’. Gernoble,

France, 6-11 April 2011

Todorova, Maria. Imagining the

Balkans. Oxford University Press, 1997

Young, E. James. “Memory and Counter-Memory”. Harvard Design Magazine, vol. 9, 1999, pp. 20-29

Stierli, Martino and Vladimir Kulić. Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948-1980. The Museum of Modern Art New York, 2018

Surtees, Joshua. “Spomeniks: The Second World War Memorials That Look Like Alien Art”. The Guardian, 18 Jun. 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/photography-blog/2013/jun/18/spomeniks-war-monuments-former-yugoslavia-photography. Accessed 7 Jan, 2019

Šuljić, Tomica. “Minirani Partizani”. Mladina, 21 Apr. 2005, pp. 66-70

Šuljić, Tomica. “Spoštuj vse mrtve”. Mladina, 6 May. 2005, pp. 17-19

Tormey, Simon. “Do we Need “Identity Politics?” Postmarxism and the Critique of “Pure Particularism””. Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions workshop on ‘Identity Politics’. Gernoble, France, 6-11 April 2011

Todorova, Maria. Imagining the Balkans. Oxford University Press, 1997

Young, E. James. “Memory and Counter-Memory”. Harvard Design Magazine, vol. 9, 1999, pp. 20-29

Žižek, Slavoj. “Tolerance as an Ideological Category”. Critical Inquiry, vol. 34, no. 4, 2008,

pp. 660-682

Žižek, Slavoj. “Multiculturalism, Or, the Cultural Logic of

Multinational Capitalism”. Confronting

Globalisation, special issue of New

Left Review, vol. 225, no. 1, 1997, pp. 28

Žižek, Slavoj. “Multiculturalism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Multinational Capitalism”. Confronting Globalisation, special issue of New Left Review, vol. 225, no. 1, 1997, pp. 28